Is the distinct dialect of Appalachia really “older than Shakespeare,” as linguists once claimed? Well, yes and no. No matter how isolated the community, no language ever stops evolving completely, and the Scots-Irish immigrants to Appalachia co-created their language patterns in conversation with other religious and ethnic groups there. It is true, however, that certain words and phrases used by Shakespeare, such as “yonder” and “afeared” are today only heard in Appalachia, a region that has held on to its folkways with great tenacity and pride, making it the special region it is.

Mountain Talk

Stretching from New York in the north to as far south as Alabama and Georgia (the boundaries are not exact), Appalachia is a cultural region mostly centered in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia and further south, to the Great Smoky Mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina. It’s a special place defined not only by its rugged mountain terrain but also by its unique dialect, which has itself been influenced by the steep hillsides and deep ravines (“hollers”) of the geography.

Linguists call it Southern mountain dialect, that distinctive combination of vocabulary, grammar, and accent that we recognize as the folk speech of Appalachia. Some examples are well known to those outside the region, such as “I reckon” (I guess, or I suppose) and “mosey” (to go to), but others are still only common in the region.

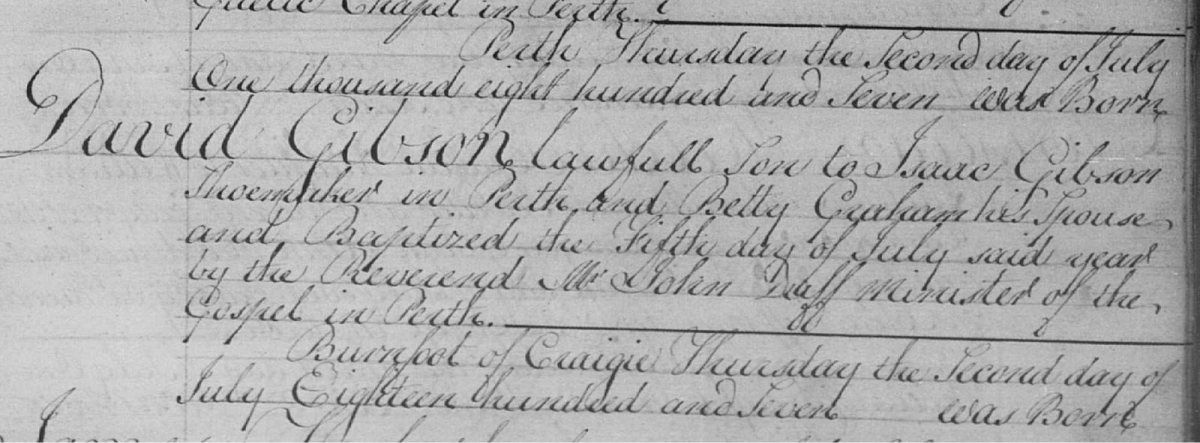

The genealogical heritage of Southern mountain dialect is primarily attributed to the influence of the 200,000 Scots-Irish (also called Scotch-Irish and Ulster Scots) immigrants who arrived in North America starting in the 18th century. The term refers to a distinct group of Protestants who, just a few generations earlier in the 17th century, were lured from the Lowlands of Scotland to the north of Ireland, where King James I of England encouraged them to colonize the Plantation of Ulster (land confiscated from the Gaelic nobility). Their Scots-Irish descendants came to America seeking religious freedom and economic opportunity, and brought their folkways with them.

One of the clearest examples of this cultural legacy can be heard in the folk music of Appalachia, much of which can be traced directly back to melodies and songs of medieval Ireland, Scotland, England, and the rest of Europe. Ballads, jigs, and reels common in these countries are still heard today in Appalachia, such as “Pretty Polly” and “Cuckoo Bird.” The influence of the music of the British Isles and Ireland is also still present in 21st century bluegrass and country music.

“Isolated from the outside world, and shut in by natural barriers,” wrote native Appalachian musician and scholar Josiah H. Combs (1886-1960), “[Appalachians] have for more than two centuries preserved much of the language of Elizabethan England.” This view of Appalachian dialect as a “pure” linguistic fossil is no longer accepted by scholars. Although many words in Southern mountain dialect do date back to 17th century England, the language is much more diverse than that. German immigrants also left their mark (the “doodle” in “Yankee Doodle” refers to a German word for a poor musician), as did the enslaved people brought to Appalachia from Africa starting in the 18th century (it was this group who introduced the banjo, an African instrument, to Appalachia). Many of the place names, such as “Appalachia” itself, are Native American words, often Cherokee, Shawnee, Creek, or Yuchi. All these influences created what is often known simply as “mountain talk” in the rural areas.

Although the Scots-Irish influence is most evident in the vocabulary of Appalachia (see list below), the pronunciation of words also reveals a connection to Elizabethan England. It was typical then to substitute an i sound for an e, as when the word “get” is pronounced “git.” This has led to additional linguistic evolution, adding what linguists call a qualifying word to help clarify meaning. An example are the words pin and pen, which often are pronounced identically. In Appalachia many people refer to a “stick pin” to differentiate it from an “ink pen,” since pen or pin alone may not be enough to communicate meaning.

Here are some more examples of “Mountain Talk:”

Afeared: scared, afraid

Airish: cool, breezy

Allow: can mean permit or let, but often also means suppose or think

Backset: Relapse (“had a backset with this illness”)

Bald: mountaintop cleared of trees (for logging or mining)

Bluff: cliff, often next to a river

Boomer: red squirrel of the Smoky Mountains

Bottom: flat land along a waterway or valley

Branch: area near a creek

Britches: pants

Courting: dating with (potentially) the intention to propose marriage

Cut a shine: to go dancing

Dope: soft drink such as Coca-Cola (also known as “co-cola” in Appalachia)

Eh, law!: Oh, well!

Fair up: when the sun comes out

Fetch: to get

Flinders: small pieces, as in “the teacup smashed to flinders”

Fornenst: can mean either “next to” or “opposite from” (as in, in front of, or against)

Gumption: spunk, daring. In 18th century England and Scotland it meant common sense.

Haet - smallest thing imaginable, from the Elizabethan phrase, Deil hae’t (Devil have it.)

Haint: ghost

Holler: steep valley surrounded by mountains

Hoove: to heave or rise

Ill: mean, bad-tempered

Ingems: onions

Jasper: an outsider

Liketa: (like to) almost, nearly

Moonshine: homemade alcohol

Mountain laurel: rhododendron

Painter: panther

Pick: to play a stringed instrument, such as a banjo

Plait: to braid

Poke: a bag or sack

Poke salad: Appalachian wild greens boiled before eating

Pooch: to stick out (origin: pouch)

Quiled: coiled.

Razor back: wild hog

Ramp: wild onion

Reverend: undiluted, full-strength (as in whiskey)

Several: may mean anything from a couple dozen to a hundred people

Sigogglin: crooked, at an angle

Skift: scattering, such as a skift of snow

Sparking: dating

Talking: serious discussion of marriage

Tee-totally: absolutely, completely

Tote: to carry

Yonder: over there

Young’un: a youth

You’ns: you (plural)

Weekly Discoveries

If any of your ancestors resided in Norfolk County, Massachusetts prior to 1900, it’s time to get excited! The Norfolk County Registry of Deeds has made available transcription of land deeds recorded in the county for the years of 1793 to 1900.

Learn more about tracing your elusive female ancestors with the webinar Forgotten Wives, Mothers, and Old Maids: Tracing Women in U.S. Research

Two Women Researched Slavery in Their Family. They Didn’t See the Same Story.

Were They Irish, Scottish, Scotch-Irish, Scots-Irish, or, as Termed by the British and Irish, Ulster Scots?

All of these terms refer to a group of settlers who came largely from southern Scotland and the areas that bordered Ireland and made their homes in the Ulster area of Ireland. They moved fluidly between the two countries and many eventually settled in America.

The Scots-Irish began arriving in Colonial America, primarily in family units. Most, but not all, were Protestant and it was not uncommon for larger groups, such as entire church congregations, to emigrate from their homeland together. There were some indentured servants in the mix, though not predominate. Most were likely drawn to America for the availability of the frontier lands. Once they arrived in America, the different families and groups tended to settle near one another, whether or not they had immigrated at the same time. This is why it is important when researching these ancestors to look at the larger family unit, as well as their neighbors and associates, as clues discovered for any of these individuals may lead to a path of discovery for a direct ancestor.

Though estimates vary, it is believed that at least 250,000, and possibly up to as many as 400,000, Scots-Irish immigrants made their way to the American Colonies prior to the American Revolution, with a large portion settling in the Pennsylvania area. Interestingly, the term Scots-Irish was not commonly used to refer to this group of people until after 1840, when waves of Irish Catholic immigrants began arriving in the United States, due to the Great Hunger (aka Irish Potato Famine). The terms Scots-Irish and Irish (or even Irish Catholic) were used to distinguish the two heritage groups. Prior to that, the Scots-Irish immigrants and their descendents were referred to as either Scottish or Irish, interchangeably, sometimes continuing well into the late-19th century.

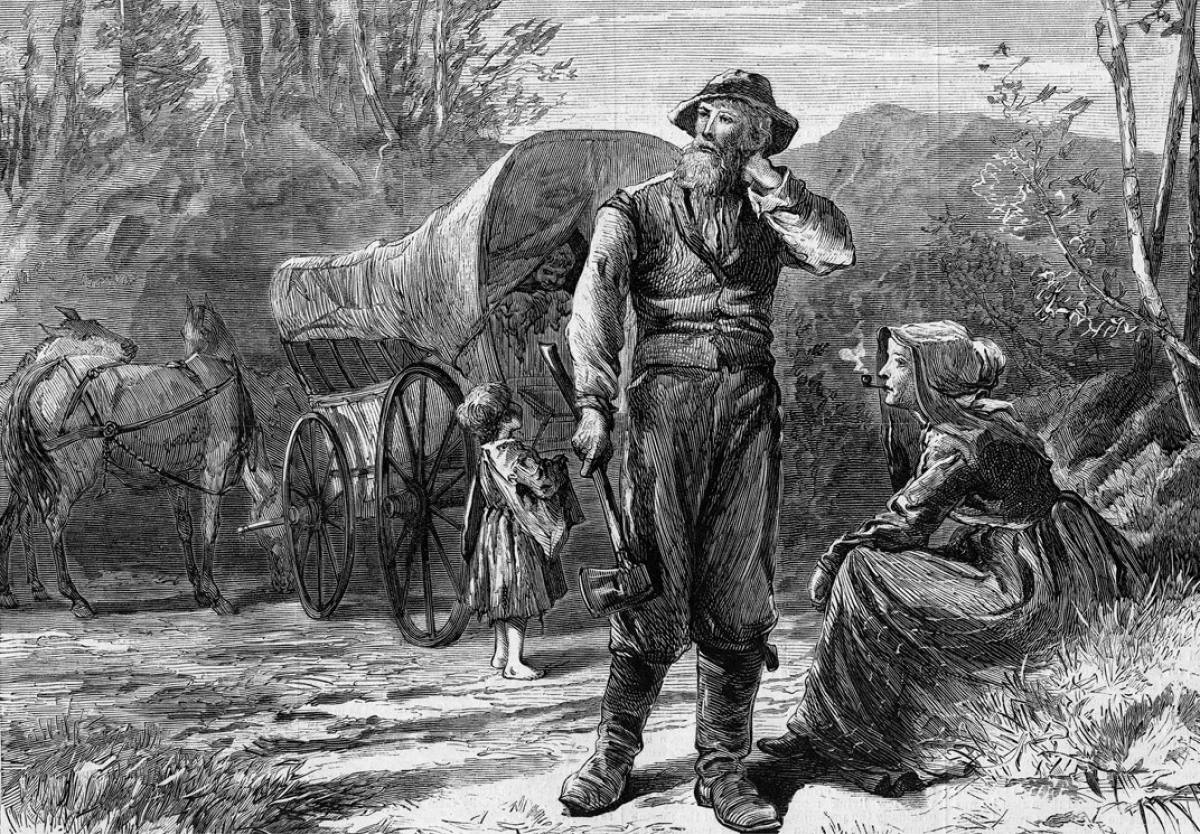

The Scots-Irish eventually migrated outside of the original colonies, many on the great Wagon Road which was originally established by Native American and stretched from Philadelphia westward, then south through Maryland, Virginia and North Carolina, eventually extending through Tennessee and as far south as Alabama and Georgia - encompassing the greater region of Appalachia It is common to find them in records recorded as native to Scotland or Ireland, sometimes interchangeably. When researching during the pre-Revolutionary War period, remember that not only was the term Scots-Irish not in use, they were not considered aliens, as they were moving to the British-controlled colonies. As such, there are no records identifying them as non-citizens.

After you have identified potential Scots-Irish ancestors, utilize traditional genealogy methods and sources, looking at the family unit, as well as their neighbors and associates. Once you have a more comprehensive understanding of the family as a whole, and possibly even have identified a specific town or village of prior residency or birth, then it is time to seek them out in the records of Ireland or Scotland. In addition to the commonly known for-fee sites, such as ScotlandsPeople, FamilySearch holds numerous record collections for Scottish research, including birth and baptismal records, marriage records and the few, but very pertinent, Presbyterian and Protestant Church records, among others. Their Irish record collections are even more plentiful and include not only vital records, but also census, wills and other beneficial records. Keep in mind that even if it is believed that ancestors were Presbyterian, they may have been recorded in the Church of Ireland records as, for a time, it was illegal to be married in another church. Later, advance notice was required to be given of Presbyterian marriages and these notices were sent to the Kirk Session. These records are definitely worth the time and effort to review, as they were sometimes very detailed in nature.

Move beyond this research primer and continue expanding your knowledge of the Scots-Irish in this free presentation. Research of ancestors of this unique culture can be challenging, but rewards can be greater!

--------------------------

Helpful Resources

The Scotts-Irish are known to have moved fluidly between Scotland and Ireland; gain insight into researching in the records of both countries with the articles Top Resources for Finding Your Scottish Ancestors and How to Find Your Irish Ancestors.

Past Issues Worth Reading

Haymarket Square Riot - Read Here

Out of Wedlock - Read Here

Legends of Ellis Island - Read Here

Outlaw Ancestors - Read Here

Adolescent Development - Read Here

German Americans: The Largest Ethnic Group in the U.S. - Read Here

Who Invented Your Telephone? - Read Here

The Boston Massacre - Read Here

Freedmen’s Bureau Impact - Read Here

Are You a Good Ancestor? - Read Here

Sources….Duh!

Wylene P. Dial, West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture and History (http://www.wvculture.org/ : accessed 6 May 2021), “The Dialect of the Appalachian People.”

Chi Luu, JSTOR Daily (https://daily.jstor.org/ : accessed 6 May 2021), “The Legendary Language of the Appalachian “Holler.”

Jack W. Weaver, The Academic Study of Ulster-Scots (https://www.libraryireland.com/ : accessed 6 May 2021), “One Old Stripper, An Old Churne, and Hanovers: Irish and Other Dialect in Blue Ridge Mountain Vocabulary.”

Cratis Williams, "Appalachian Speech," The North Carolina Historical Review, Vol. 55, No. 2 (North Carolina Office of Archives and History: Raleigh), April 1978, digital images, JSTOR (https://jstor.org : accessed 6 May 2021), citing print edition, p. 174-179.

Jennifer Cramer, University of Kentucky (https://core.ac.uk/ : accessed 6 May 2021), “Is Shakespeare Still in the Holler? The Death of a Language Myth.”

Appalachian State University, Special Collections Research Center (https://collections.library.appstate.edu/ : accessed 6 May 2021), “[Documenting Appalachia.”

PBS (https://www.pbs.org/ : accessed 6 May 2021), “Smoky Mountain Speech.”

Walt Wolfram, "On the Linguistic Study of Appalachian Speech," Appalachian Journal, vol 5, No. 1 (North Carolina Office of Archives and History: Raleigh), 1977, digital images, JSTOR (https://jstor.org : accessed 6 May 2021), citing print edition, p. 99-102..

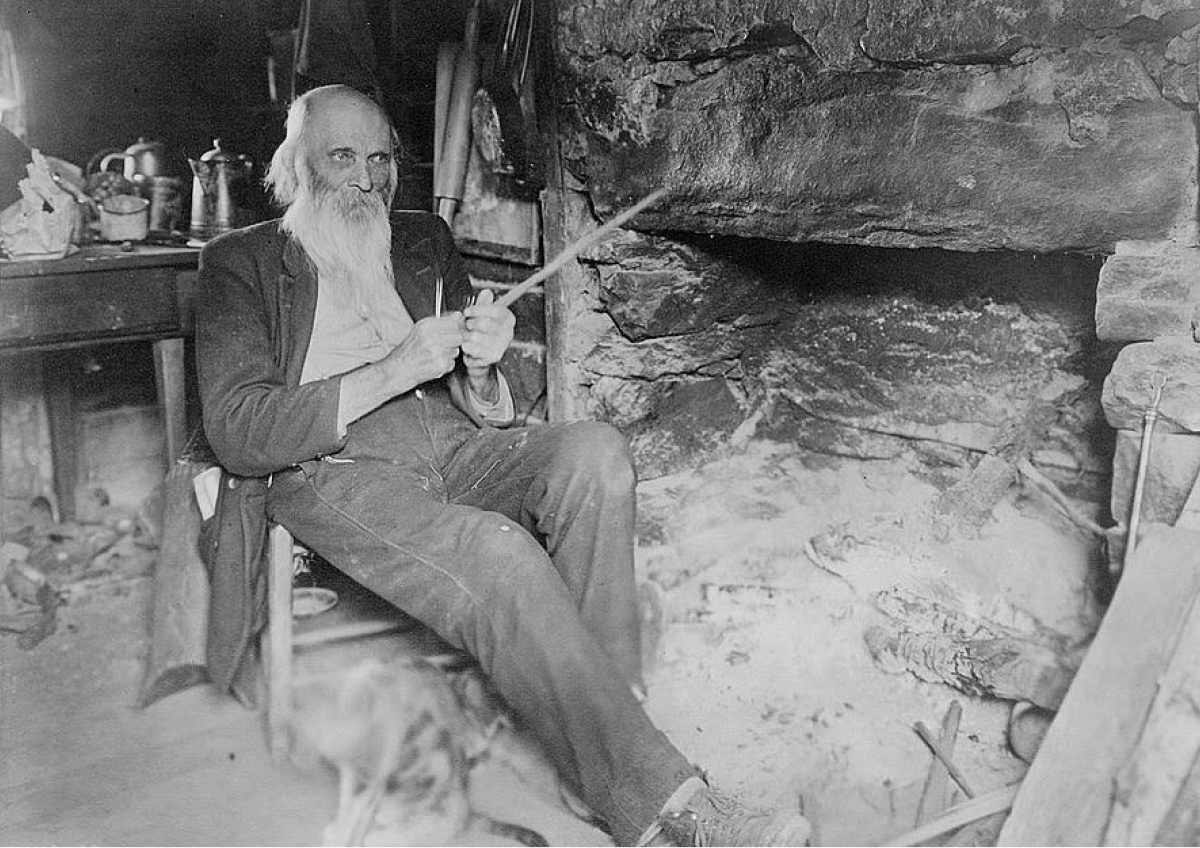

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, digital images, Library of Congress (https://loc.gov : accessed 6 May 2021), digital image from b&w negative, “Mountaineer whittling,” unknown date, (Chicago: Inter Ocean Co., [1886]) digital id cph.3c18644.

Wikimedia Commons, database with images (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:OP 13 Country Store and Emigrants Noonday Hault (9091286045).jpg : 6 May 2021), digital image of original illustration, “File:OP 13 Country Store and Emigrants Noonday Hault (9091286045).jpg;” image uploaded by user Fæ.